Those who are worthy wait, those who are unworthy never hesitate.

That is the thought that came to me while watching The Boy and the Heron, the new film by Hayao Miyazaki, the legendary animator and masterful weaver of fairytales. The words seemed strange at first, but the idea arrived when Mahito—the main character and avatar for Miyazaki—hesitates to take power in a situation he’s uncertain of. That hesitation proves he’s a worthy hero, and it comes in contrast to other characters who destroy with a sense of entitlement.

That’s what Miyazaki-san does, he causes us to question the nature of our motives and the impact of our intentions. As humans, we constantly sift through a cascade of emotions; for Miyazaki what matters is how we reshape the world in response to our joys, our rage, our dreams, or our grief. This is his ministry. He is so adept at presenting our struggles through the filter of fantasy that we might be tricked into disbelieving their reality.

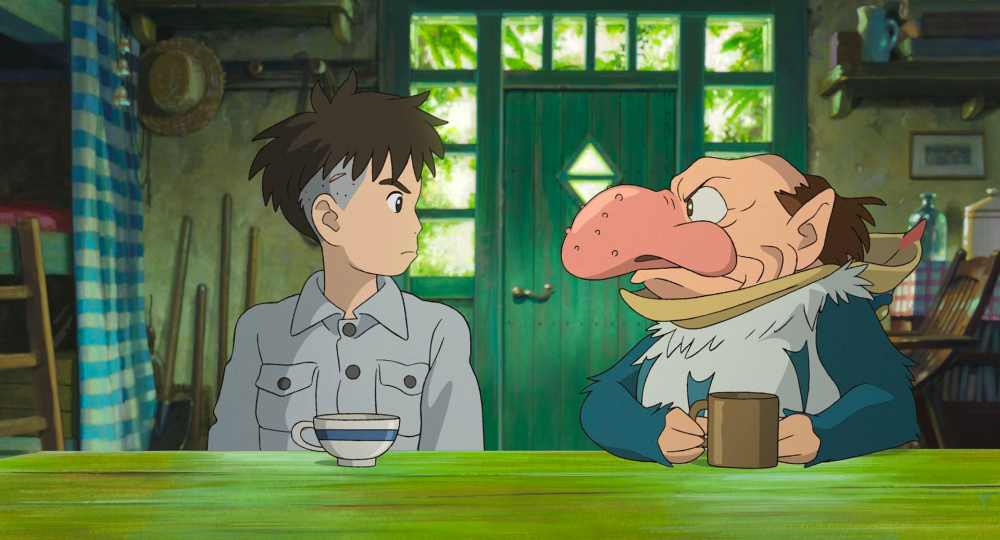

The Miyazaki-style of animation doesn’t just enhance his storytelling, it adds facets. Even when his movies are mid (of which there are very few), Studio Ghibli’s craft is so lofty they upgrade mid into mastery. It’s in the inventive ways creatures and things move. The Heron doesn’t just transform into a man, it coughs him up and swallows him again as needed. The Boy doesn’t just retreat from hiding in the shadows, he slinks backward like a feline. Miyazaki-san never settles for mundanity when quirk and mischievousness are possible.

Here, the story centers on Mahito (Soma Santoki), who suffers alongside his father after his mother is killed in an air raid. His father recovers quickly, primarily by marrying his wife’s younger sister, but Mahito remains out of step with the world. He mourns by bottling things up. When father and son move to Mahito’s maternal ancestral home, a family curse or perhaps affliction rises again. There’s a great-uncle who had an obsession with a nearby tower and was swallowed up by it. For a time, when she was young, The Tower took Mahito’s mother too. Yet a gray Heron (Masaki Suda) insists she is still alive out there, somewhere. And because we cannot escape the debts that heritage calls due, Mahito is eventually consumed by The Tower and transported to a fantastical realm where life, death, and time are merely suggestions.

In The Boy and the Heron, titled How Do You Live? in Japan—in deference to the novel by Genzaburō Yoshino—Miyazaki returns to the markers of his style. A young person (a boy this time but traditionally a girl) dealing with the repercussions of war and the portal fantasy through which they escape—but only for long enough to understand their world and possibly edit their place in it.

No one does it better. Yet this film is personal. Through The Boy and the Heron, Miyazaki-san is seeking to reconcile the grief that remains after the death of his mother, and the recent loss of his greatest collaborator and friend, Isao Takahata (Studio Ghibli co-founder). The movie is emotional and yet unfurls unevenly because of this. Mourning will always tell its story in its specific way—often when grief pours out it overflows in a stream of consciousness that cannot remain bottled up. Luckily for us, an unstoppered Miyazaki-san still intoxicates.

See it because it’s a Hayao Miyazaki film and that is enough.

filed under: ANIME